So I started thinking about how to explain what brought me to the conclusion that knowledge is a commodity and how LRNGO.com was going to implement a platform for this, and I realized that it has actually been a common theme throughout my life. Of course, the purpose of this blog is not to bore you with my life story, but…well, too bad I’m going to bore you with my life story. 🙂

It all started with music. Like a lot of kids, I gravitated towards what I was good at. In my case, when I was growing up and heard songs I liked on the radio, I could usually play & sing them by hearing them. It was just something I did and enjoyed without very much difficulty. When I “learned,” it was because I was either learning through private instruction, or performing with others who were older and better than me. Research was practicing, learning from an instructor was training, but playing for and with others actually “doing it” was social and learning at the same time. That’s what provided the benchmarks, as well as the impetus for me to research and train harder.

This early experience eventually led me to write a thesis called “All the World is a Stage: the Dynamics of One on One Training vs Group Immersion.” The idea is that you train more intensely one on one so you can interact at a higher level when you are in a social group, and the larger the group (or “stage” so to speak – expandable up to the whole world), the more competition, and therefore the more intensely you train. I hypothesized that one could apply this to all forms of learning; everything from the Olympics to languages (ie: if you are in France, you will not only learn French quicker because you are there “doing it,” but also because you will try harder to learn when you are training).

Whether or not the idea that effort or assimilation is directly proportionate to competition and size of a group is flawed, what I found interesting was the extent to which these dynamics feed off of each other and how they are inter-related, and the percentages of learning that take place in social group or immersion settings vs one on one training vs research/practice. At the time though, I didn’t acknowledge the extent to which one on one learning is also social–which brings me back to…that’s right, my boring life story. 🙂 (Stay with me here, it will all make sense.)

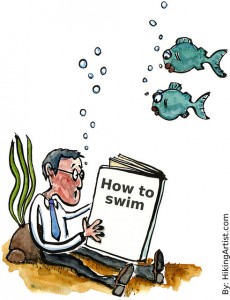

I earned money to go to college by gigging in professional bands the summer before and the summer after my first year of college. Without getting into how much I learned performing vs how much I learned in school (almost equal but very different), at that time, I chose to continue to play professionally rather than complete my degree. However, a few years later as a professional, I found myself having to compete with better players on larger stages, and felt like I would have also greatly benefited from a strong university program. Unfortunately, the choices at that point weren’t good for a working musician. To stop working full-time and go into debt for school was not a viable option on a musician’s salary.

Looking back now, the situation reminds me of a story I heard. There was this guy who wanted to go to MIT (skip ahead if you’ve heard this one before) but couldn’t get in and didn’t have the money. He borrowed a small amount to attend a nearby Art Institute and learned how to create a very realistic school ID. He used his skills to manufacture one for MIT and attended their classes, and although he never got credentials on paper, once he started working in the real world no one cared. He took his studies seriously, and became a good enough software engineer that he always had work. He had no money, learned, and ultimately beat the system. (I wouldn’t have tried this myself, because with my luck I would have just ended up in the slammer owing a lot of money to MIT!)

So I didn’t plan anything near as devious, but I did contact the professor at my target university who was the head of the department directly. I explained the situation to see if he would teach me privately, and he did. I learned the curriculum directly from him (a credit to both his goodwill and teaching ability), and reaped the benefits in less than one third the time at a small fraction of the cost. What I didn’t realize at the time, was that I had also accidentally learned how to teach the curriculum that he taught me. I found this out later, and then began teaching what I knew to others through private lessons.

From that experience, the questions eventually started pouring into my head. How closely are learning something and learning how to teach it related? Was it just me, or can anyone transfer one to the other? (Still an ongoing question BTW.) If I learn “how to teach”, can I then teach anything I learn? For me it stood to reason the answer was yes, but I wanted to find out. I did, and eventually became a full-time instructor.

At one point I may have gone a bit far in my experiments, and I began teaching in classrooms when I had little (ok no) credentials for this. I did know the subject, but had no classroom experience or training, so I decided to do some preliminary consulting with the best classroom teachers I could find to learn a thing or two before going in. After a couple weeks, I quickly found a job where they had been through three teachers in the past 18 months (it turned out none of them could keep the class engaged – baptism by fire!), and I just started “doing it.” Sure I made mistakes in the beginning, but I made sure to document everything and keep track of what was working and why. In the end, I turned out to be the first teacher for that subject and in that school location they had ever considered successful, and I continued at the school for two years.

As another side note (can I do that? Where is the blog handbook…): I have to say IMHO other than knowing the subject matter, a short stint in comedy turned out to be the best training possible for me as an uninitiated teacher going into a first time classroom setting. Not to entertain or even to keep attention of the class, but because it constantly makes one hyper-sensitive to gauging audience reaction and instantly knowing if they are “with you” and “getting” what you’re saying. In comedy, if the audience doesn’t understand or “get” something, seconds seem like hours, so you learn to redirect them and communicate very quickly in a different way that makes you understood or else you “die.” If I had one bit of out of the box thinking advice to universities, I would encourage experimenting with limited standup comedy training in education curriculums and then measuring results. (I’d be very interested to know if anyone is actually out there doing that!)

Anyway, all that is to say, my own private instruction experiences ultimately weren’t just social because I was interacting with another person when learning, but because there was also a paying it forward aspect from teaching others in turn.

And so it went: from martial arts to business accounting to running a record label, I always felt like given time and money limitations, I got more bang for my buck by just doing things and paying an expert of my choosing to teach me how. This, in turn, also helped the individual instructor to supplement their income at a time and location that was convenient for them, and eventually enabled me to pass on to others what I had learned in the new role of instructor. No, it shouldn’t be the only way—but it should be a choice everyone has—whether used to supplement their classroom experience, or to learn a new skill on the side. It is the future, and the future of education will be about choices.